Should SF tax empty homes and buildings?

San Francisco Supervisor Aaron Peskin has asked the city attorney to explore legislation to impose a vacancy tax on large property owners who leave residential and commercial buildings empty.

During a supervisors meeting this month, Peskin said he continues to receive complaints about the impact of “ghost buildings” on neighborhoods.

The problem is, nobody really knows how many vacant homes there are in the city and whether a vacancy tax would be legal or effective in freeing up much-needed housing.

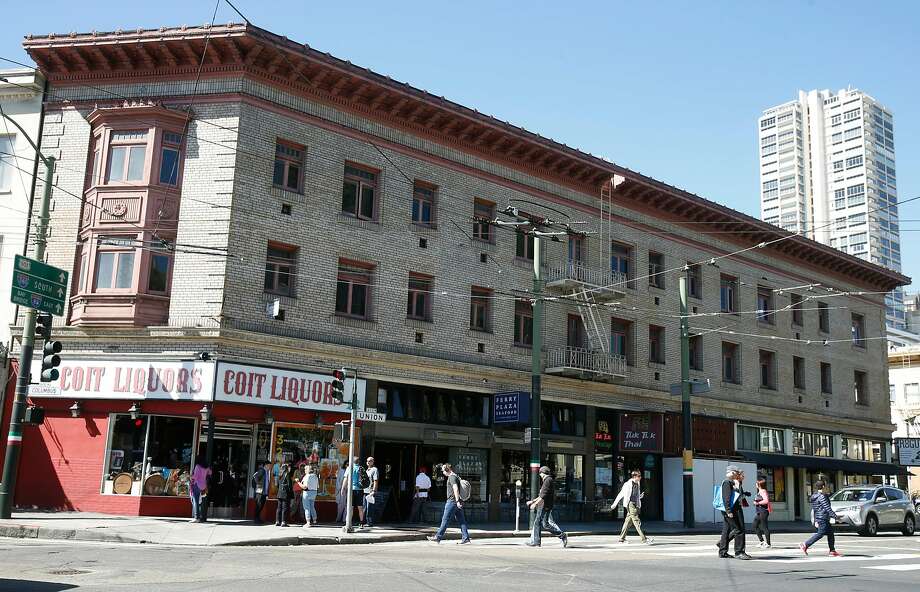

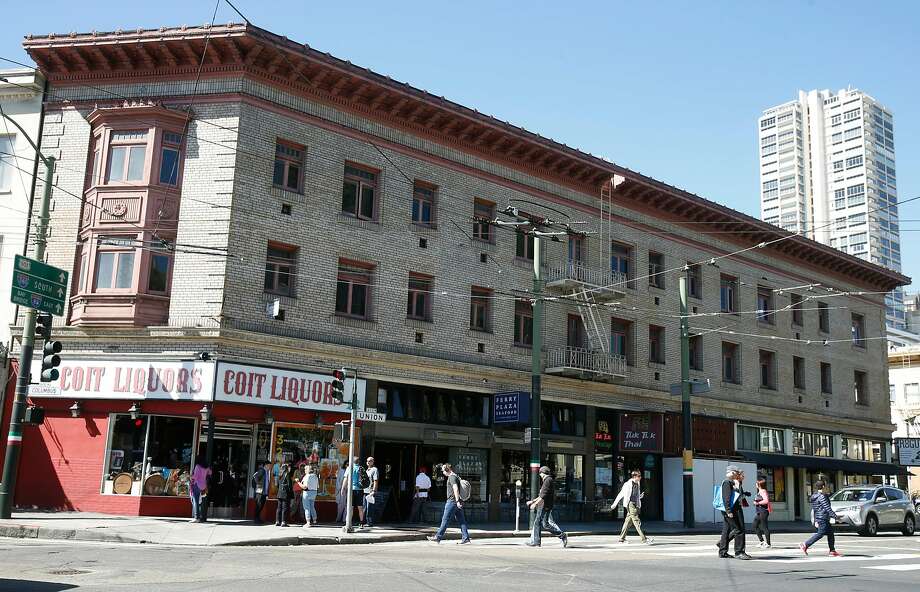

In an interview, Peskin cited a 28-unit apartment building at 1656 Powell St. that was vacated after a fire damaged some units in December 2013. It remains empty. The three-story building is in a prime North Beach location across from Washington Square Park.

Four businesses on the building’s ground floor — a liquor store, a bar, a Thai restaurant and a seafood restaurant — are open, but the apartments above still have boarded-up windows and a littered lobby. Some work was done in the units in 2015 but never completed, according to the building department.

Shadi Zughayar, who runs Coit Liquor on the street level, thinks a vacancy tax would bring tenants back. “I love this building,” he said. “I want it to be active, not like pigeons living there.”

The building is owned by an extended family whose members could not be reached. “The owners have been working together to repair the property ever since (the fire), and we all look forward to the day when the tenants can move back in to the building,” said J. Timothy Falvey, a senior vice president with Hanford-Freund, which manages the commercial space. His firm is not involved in the reconstruction and couldn’t comment on it.

Adil Shaikh, who managed the residential portion under a master lease, said some of the former tenants are eager to return, and he doesn’t know what is taking so long.

Landlords might keep apartments empty for any number of reasons, Peskin said. Maybe they had a bad tenant and don’t want to risk another, or they are holding property as an investment and “just don’t care” about forgone rent. “I asked the city attorney to see if we could propose a tax,” to encourage property rentals.”

Around the world, some cities have considered or imposed vacancy taxes to fight blight, free up housing or discourage foreign investors from using real estate as a piggy bank or money laundering facility.

In January, Vancouver, British Columbia, imposed an “empty homes tax” equal to 1 percent of assessed value on non-primary homes and rental units that are not occupied for at least six months of the year.

Vancouver’s City Council enacted the tax even though a study it commissioned that analyzed electricity use found that the non-occupancy rate had been flat at around 4.8 percent from 2002 to 2014 and was in line with that of other Canadian cities. “However, the report still indicated the presence of (an estimated) 10,800 empty properties in Vancouver — and census data suggests that an even larger pool of underutilized properties may exist,” a Vancouver spokeswoman said in an email.

Some cities in France and Australia have imposed vacancy taxes, and some in the United Kingdom are looking at it. Washington, D.C., levies a higher tax on vacant property ($5 per $100 of assessed value) and blighted property ($10 per $100 assessed value) than on occupied property (85 cents to $1.85 depending on use).

abandoned apartment building at Columbus Avenue and Union Street in San Francisco. The large building has remained vacant after a fire caused damage in 2013. Photo: Paul Chinn, The Chronicle" /> Photo: Paul Chinn, The Chronicle

abandoned apartment building at Columbus Avenue and Union Street in San Francisco. The large building has remained vacant after a fire caused damage in 2013. Photo: Paul Chinn, The Chronicle" /> Photo: Paul Chinn, The ChronicleAn abandoned apartment building at Columbus Avenue and Union Street in San Francisco. The large building has remained vacant after a fire caused damage in 2013.

In San Francisco, owners of vacant properties are supposed to register with the city and pay a $711 annual fee. As of May, there were 38 residential and 47 commercial properties on the registry (excluding ones that had received exemptions or become occupied). However, the registry is not a complete inventory because the city relies on self-reporting and complaints to identify vacant buildings. The Powell Street building is not on the list, although the ground floor is occupied.

SPUR, a Bay Area nonprofit focused on planning issues, used census data to estimate the number of non-primary homes in San Francisco, meaning those not being used full time by owners or renters for reasons other than natural turnover, foreclosure, construction or certain other factors. In a study published in 2014, it found that only 9,100, or about 2.4 percent, of the city’s total housing units (rental and owner occupied) were used for “seasonal, recreational or occasional use.”

Compared to other high-cost markets such as Miami, Honolulu and Manhattan, San Francisco’s percentage of non-primary residences is relatively low, the report said.

SPUR also tried to determine whether San Francisco’s rent-control policies keep units off the market by comparing vacancy rates in the city to surrounding counties, but found the results inconclusive.

“We found it extremely difficult to figure out the size of the (empty-home) problem,” said Sarah Karlinsky, one of the authors. But based on the data SPUR analyzed, “it didn’t seem to be huge.”

The city has passed regulations to crack down on homes being used as full-time vacation rentals through companies such as Airbnb.

A warning notice is attached to the front door of an abandoned apartment building at Powell and Union streets in San Francisco.

A warning notice is attached to the front door of an abandoned apartment building at Powell and Union streets in San Francisco.

Photo: Paul Chinn, The ChronicleNeighborhood teens walk past the entrance of an abandoned apartment building at Powell and Union streets in San Francisco.

Neighborhood teens walk past the entrance of an abandoned apartment building at Powell and Union streets in San Francisco.

Photo: Paul Chinn, The ChronicleA room buzzer panel is devoid of tenant's names at the entrance to an abandoned apartment building at Powell and Union streets in San Francisco.

A room buzzer panel is devoid of tenant's names at the entrance to an abandoned apartment building at Powell and Union streets in San Francisco.

Photo: Paul Chinn, The ChronicleA vacancy tax has not been tried in California. If San Francisco decided to impose one, the city could minimize the risk of a legal challenge if it were structured as a parcel tax and won voter approval, said Darien Shanske, a law professor at UC Davis. Structuring it like Vancouver’s could be a problem, because under California’s Proposition 13, taxes based on the value of a property cannot exceed 1 percent of assessed value.

Implementing a tax could be a burden for property owners. In Vancouver, every homeowner must submit a form online once a year indicating whether the home was occupied or rented and for how many months. If they don’t submit the form, it will be deemed vacant and taxed. If they do submit it, and are selected for audit, they must provide proof of residence or rental. The city expects to spend $4.7 million over three years to implement the tax.

And there’s no guarantee it would free up more housing. Some people might just pay the tax or find ways around it.

For single-family homes and condos, having a tenant in the house is “the single biggest issue,” for buyers and sellers, said Patrick Carlisle, chief market analyst with Paragon Real Estate. “You can’t stage it, you can’t clean it up, showings are more difficult. The great majority of people won’t consider buying a tenant-occupied house because of the significant cost, hassle and liability factors of eviction in San Francisco. The buyers who will consider it want a substantial discount.”

In San Francisco, a vacancy tax could be a solution in search of a problem, said Richard Green, director of the Lusk Center for Real Estate at the University of Southern California. “If this were really a problem you would see high vacancies, and we see very low vacancies in the Bay Area,” he said. “San Francisco’s principal housing problem is not that its housing stock is not being fully used.” The real problem: “You need more of it.”

Kathleen Pender is a San Francisco Chronicle columnist. Email: kpender@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @kathpender

Comments

Post a Comment